![]() zurück zur Liste der Grundlagentexte

zurück zur Liste der Grundlagentexte

Wolfgang Martin Stroh:

Migration and Music Education in Germany

- “All is said, but nothing is done”

1. Concepts of Intercultural Music Education as a Response to the four Phases of Migration in Germany

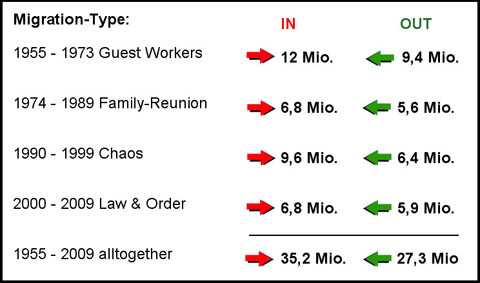

Although the German situation of migration offers some special features, I hope that there will be problems and solutions, which are of an European interest. I refer here to music education in public schools. 9 Mio. students visit these schools, and among them there are 2.34 Mio. students with a migrant background (and 0.9 Mio. Muslims)[ 1]. The different concepts of music education, which are concerned with migration, are a response to the four phases of migration in Germany:

- 1955-1973 (guest workers)

In the phase of “Guest Workers” 12 Mio. foreigners from Mediterranean countries worked in Germany. These workers had fixed-term contracts, so that their relatives stayed at home. Therefore there were no foreign kids in German schools. German popular music shows very highly welcome. The musical life of these guest workers was completely isolated from the German society, and it took me considerable effort to get a recording of a Yugoslavian party near Karlsruhe in 1973.

Video 1: "Ein kleiner Italiener" and field recording.

- 1974-1989 (family reunion)

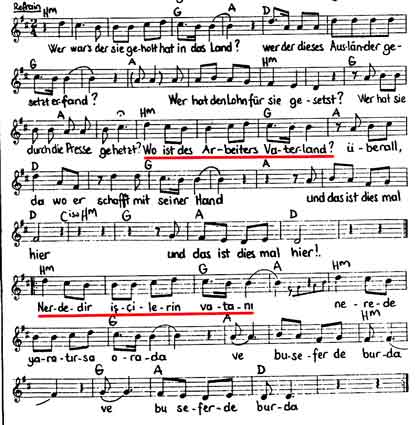

The Federal Republic stopped any further recruitment of foreign labor in 1974. 2.6 Mio. guest workers remained in Germany, among them 0.65 Mio. Turkish. They drew their families into Germany, or started their own families. Thus foreign kids appeared in public schools. In the 1980’s , we had a vivid foreign subculture, which interacted with the dominant German music scene within a small politically engaged sector. By 1976 there was the only worldwide Turkish Worker’s choir in Berlin lead by the exiled composer Tahsin Inciri singing for a German audience. Turkish-German Song-Books were published, for example one of Zülfü Livaneli (1981). Other song books were printed for the use in Kindergarten and Elementary Schools. One could also hear bi-cultural concerts within the German left-wing scene:

Music Example: Mesut çobancaoğlu & Frank Baier "Türkçe ve Almanca şarkılar" 1986.

Many foreign kids were referred to Schools for the Handicapped (Sonderschulen), because of their lack of knowledge of German language. The music teacher Irmgard Merkt from Dortmund recognized that these kids were not stupid or handicapped. She wrote a book on the situation of “Turkish-German Music-Pedagogy”, and this was the beginning of Germany’s “intercultural music education” (IME)[ 2]. Her aim was intercultural communication by musical means. At that time nobody talked about social integration, as is the case today. This feature corresponded to official guide lines to maintain “the ability of move back to the homeland” (Rückkehrfähigkeit).

The leading ideas of this IME were transformed into contexts outside public schools. Let me give an example: The “Cultural Cooperative Ruhr” (Dortmund) organized in some dozen cities music groups called “rüzgargülü”. These groups sang and performed strictly bi-lingual, and addressed foreigners as well as Germans. They sang songs, which were known by the foreigner’s children (in Germany), and not songs, which music ethnologists had found in villages of Greece or Turkey. Let me show an example: the song “dere geliyor dere” first sung by a Turkish child and then a version of a group “rüzgargülü”:

Video 2: “rüzgargülü” - “Dere geliyor dere” field reording and concert

Irmgard Merkt’s concept of IME had almost no importance within the main discourse of German music pedagogy. The teachers of the 1980’s were engaged in learning how to teach Pop-Music instead of Art-Music. And thus, they had to learn about Jazz, Soul, Blues, Son, Salsa and other Latin Styles, Afro-Pop and Afro-Percussion. They did not learn about the music of the main migrant groups living in Germany. Thus they established some kind of “Alibi-IME”. (This Alibi-IME is predominant up to our days.)

- 1990 – 1999 (chaos)

Due to the “Wende” 1990 the German Policy concerning migration fell into chaos: between 1991 and 1994 1 Mio. immigrants entered Germany per year, almost half of them from East-Europe, who were called “Re-Settlers” (official term 2008: ethnic German immigrants from Eastern Europe), i.e. persons mainly from Russia whose ancestors settled East in the 18th century. Besides this, the Balkans-wars produced some millions of refugees or asylum seekers. For example, in 1992 there were 0.4 Mio. asylum seekers.

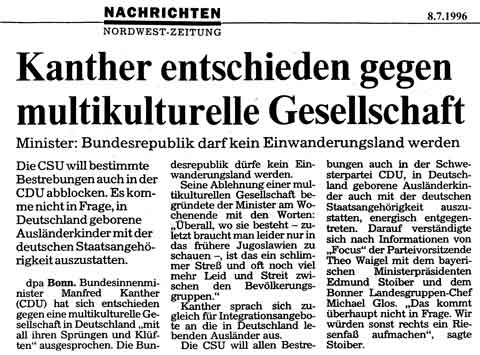

The Federal Government still refused to acknowledge that Germany is a multicultural “immigrant country”, and the Minister of Interior said: “Let’s never become a multicultural society, because this means much pain for the peoples as is the case in the Balkans”. A new notion came into use, the German “guideline culture” (Leitkultur)[ 3]. This notion means more then just follow the German Constitution[ 4], but there was never a clear, non-ideological definition.

In these years German music pedagogy started for the first time an intense discussion on music education within public schools, which are affected by migration and are actually multicultural. This discussion was an intellectual and humanistic reaction to the policy, which was characterized by Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s strategy “wait up, do nothing, and see what will come”.

The concept of IME from the 1980’s was no more sufficient, because this concept had assumed that in a classroom there were only two homogenous groups – Germans and foreigners. But actually there were grandchildren of guest workers (speaking one of the many German dialects), some “re-settlers” from Russia (with German passport but without knowledge of the language), refugees from the Balkans with their war trauma, African children with the typical racist discrimination, Arab asylum seeker’s children (from Lebanon, Iraq, Sudan, Eritrea etc.), “boat people’s” kids from Vietnam etc.

Thus two new concepts were developed within the 1990’s:

(1) The transcultural music education, which addressed all students: the migrants and the non-migrants, the foreigners and the Germans. The aim was not anymore an intercultural communication process but the experience and self-awareness of the “global character” of musics. Thus, the music dealt with was mostly archetypical. Volker Schütz demonstrated his concept by using African Music (“authentic” and “popular”). He said that the “body character” of this music is the basis of the popular music, which all kids living in Germany are more or less acquainted with.

The transcultural concept was fascinating to music teachers, as they didn’t have to learn much about Turkish, Arabic, Indian, Chinese or Indonesian music. They could continue with afro-percussion or samba-dancing, which they have learned in the 1980’s.

(2) The (sub)cultural oriented music education was a general music educational concept. The different migrant’s music cultures were considered as one of many possible musical subcultures. Even the German kids live within more then one music subculture. Thus, dealing with music subcultures would cover all needs of the migrant students.

This concept was very convincing, but nevertheless so demanding, that it was realized only within some projects and never had a wide response[ 5].

- 2000-2010 (law & order)

The year 2000 was a turning point within Germany’s migrant policy. In this year the “Nationality Law” was passed, and this law substituted the “Reichsverordnung” of 1913! Now, the principle of birthplace (jus soli) was introduced, which means that a child born in Germany is German until the age of 18.

In the year 2005 the first “Immigration Act” (Zuwanderungsgesetz) in Germany’s history went into effect. This Act did avoid the German notion “immigration” (Einwanderung) and used the term “into-migration” (Zuwanderung).

In addition to these two important Acts, the National Statistics started to consider people with a “migrant background” – short “migrants” - instead of “foreigners”. In Germany there live 7 Mio. foreigners, but more then 15 Mio. migrants.

All the conflicts which were described by sociologists in these years and which appeared even in the music classes, got a shocking interpretation by PISA in 2000, 2003 and 2006. The PISA discovered that in no other OECD-country the chances of getting a good education are more dependent on the social status of the students as is the case in Germany. Thus it was evident, that students with migrant background also had fewer chances within Germany’s education system as others. Additionally within the very last years it was stated, that within the group of students with migrant background the Turkish students are significantly underprivileged, whereas other migrant-groups do quite well.

As a response to this situation I formulated the concept of “multicultural music education”. The aim of this concept was

that students should be educated as “responsible citizens” (mündiger Bürger) with the “competence of multicultural activity”. This means to be able to act in an active, conscious, self determined and social way within a multicultural society.

This concept states that Germany is a multicultural society, and that it is important to learn how to “handle” this society in a responsible and self determined way. It was applied to one important sector of cultural activity, music. Listen to AzizaA, a Rap-Singer from Berlin, who calls her audience to become multicultural competent:

Video 3: „Es ist Zeit!“ by Aziza A.

2. The decline of the multicultural concept

There are two reasons, why this concept was never completely accepted by music pedagogy within the actual debate on integration:

- First: Music Education after PISA

One of the results of PISA was, that German’s youth is very bad equipped for a life in the modern global world. The political debate following this result culminated in the promotion of the “hard skills” – math, language, nature science – in public schools. Therefore the “soft skills” together with art, dance and music had to legitimate their mere existence. Concerning music education, a severe struggle to survive began. This had two consequences:

First, music pedagogy research concentrated on the investigation of “effects of transfer”. Some tried to proof that the IQ might increase by musical instruction, others found that social behavior gets better, and even others said, that the learning of languages will be smoother if one plays an musical instrument.These arguments of transfer are good for politicians and a stupid public opinion, but not as arguments for professional music educators. Music educators prefer another, so called “inner-musical” way of rescuing:

The name of this (second) way is “JeKi” what means “every child an instrument”. The program is to install so many musical instruments in Elementary Schools that every child can get instrumental instructions for about two years. As this concept arose on the background of the fact, that in German Elementary Schools only about 25% of the needed music lessons are realized, “JeKi” covered four demands: first to satisfy angry parents, second to be an 100 Mio. Euro-investigation of Germany’s music industry, third to give a popular answer to the “PISA-attack” on art and music, fourth to engage non-academic teachers, which are cheaper.

Both ideas are no useful concepts of intercultural music education, and not a profound answer to “music and migration”. Their motto is: making music is good in any way, no matter what kind of music or what cultural context. Of course, these ideas can give an attribution to the actual debate on integration. If kids with different ethnic background play together in a music group, integrative aspects will play a role. But nevertheless, these rather diffuse effects do not constitute a concept of intercultural music education.

- Second: The Policy of Integration instead of Multiculturalism

In the year 2006 German media and the responsible politicians proclaimed, that integration has failed in Germany. The Federal Chancellor constituted an “Integration Summit” (Integrationsgipfel). Two causes of the proclaimed failure were discussed: first that the migrants are not willing to integrate themselves into the German society, second that the idea of multiculturalism was wrong.

In 2007 the Federal Government started the “Nationwide integration program”. This program is a typical policy for managing a status quo, which is due to a long history of political mistakes concerning migration. The traditional self-image of the Germans shall not be questioned. Migration is considered as an economic chance, not a chance of cultural enrichment. Concerning culture, migration remains an unavoidable problem.

The actual policy does not deny that Germany is multicultural. But the aim of the policy is to change this. Germany should be plural, democratic and liberal. Different cultures should act under the roof of the German “guideline culture” (Leitkultur). Only very view people try to formulate aims which go beyond the actual debate, for example when sketching a society and a school system where people can speak different languages without being discriminated[ 6].

- Music Education and Integration in Germany today

Let’s have a look at the actual “Nationwide Integration Program” 2007. It is based on two pillars:

- the concept of nationwide “Courses of Integration” and

- the support of “models” or projects which show integration within informal groups and organizations.

(1) The Courses of Integration cover 600 units of language-instruction and 45 units of “basic orientation”. This facts mirrors the opinion that the knowledge of the German language is the only key to integration. I doubt that this opinion is useful. The competence of acting self-determined within the society depends not only on the knowledge of German language but also on a profound cultural knowledge. As Germany still is multicultural this competence is a competence of multicultural activity just as the concept of multicultural music education says. So far there are no nationwide concepts for the inclusion of multicultural perspectives into the Courses of Integration[ 7].

(2) The second idea of the new “Nationwide Integration Program” is to support projects, which bring organizations of the migrants together with German organizations. There are lots of organizations within the migrant communities. For example, the music life of the Turkish community is very wide spread, reaching from traditional folk- or dance-clubs to choirs, private music schools, studios, discotheques, concert managers, music groups, music soloists etc. Nevertheless, this music life is amorphous. And it has still hardly any connection to the very good organized musical life of “official” Germany. Let me show one example:

Video 4: Turkish Music School in Oldenburg

The “Turkish Music Conservatory” of Oldenburg exists since 1999. The organizer’s aim is “to remind the kids of their tradition and to keep them away from the road”. He never dared to cooperate with the Music School of the Oldenburg Community, although some of his students learn in this German institution. And a higlight of his activity was, when I (as professor from the University) did visit and record his rehearsals and concerts.

This example shows that there is a need of better contacts between the informal multicultural life of migrants and the established German institutions. Every official support of contacts will be usefull.

Nevertheless this support is necessary but not sufficient. Still the most important places where different cultures meet one another are the public schools. Music education within the public schools is the basis of all the spectacular projects of cooperation. But music education in public schools is not yet part of the Federal integration program. The Federal Ministry of Migration and Refugees has not yet discovered the integrating power of music, as a member of the Ministry told me some weeks ago. And the music teachers have other problems then considering special cultural needs of migrants, as I mentioned above.

3. Finale: “something is done…”

The discussion on migration within the community of music educators seems to be finished: “All is said”. But still, it seems, that nothing is done.

Politicians like to support spectacular project, which win prizes and can be observed by the media. Politicians do not like to support the basic work of teachers at public schools, as this is very expensive and has little response from the media. As You might know, Germany’s financal support of the education system is on the European wide lowist possible level, and within the three last years these expenses even dropped slightly. Thus, music education in public schools plays no role within the actual discussion on integration and migration.

But let me mention an example of intercultural work, which connects the project-concept of the “Nationwide Integration Program” with basic teaching in public schools. And which shows, that still something is done. Near my town Oldenburg, there is a camp for asylum seekers. The office “IBIS” which is responsible for carrying out the integration courses also takes care of the asylum seekers and supports them on their way trough the institutions. Besides this, the office makes arrangements for – mainly African - asylum seekers to teach music and dance in public schools. And last but not least, just four weeks ago, they showed an “experimental musical”, which was performed by a group of asylum seekers, three professional Rap-Dancers and one German teacher. Here we had an ideal connection of music education in public schools, which profits from the musical abilities of migrants, and a spectacular musical project supported by the Federal integration program.

Video 5: IBIS-Musical with asylum seekers[ 8].

This text was the manuscript of of speech held as key note on the 18th Congress of European Association of Music at School at Bolu, Turkey, April 29, 2010. There exists an extended Multimedia-Version. Please ask, if You wish to get this DVD (5 Euro within Germany, 8 Euro within Europe including Turkey). The text will be published in an extended version in the Congress Manual.

Footnotes:

1 The aim of music education in public schools is not the ability to play an instrument. For instrumental instructions we have the so called “Music Schools” and a System of private teaching.

2 Please note: in Germany the complete complex of music pedagogy concerning with migration is often called IME. See my page www.interkulturelle-musikerziehung.de, which should covers als concepts possible.

3 “guideline = Leitlinie is the main association in the new term Leitkultur. But Leo-Dict :„German values as guideline“, „German cultural identity“, “defining culture” (Washington Post).

4 Today, naturalization is only possible if one accepts the Constitution (f.ex. equal right for men and women, religious tolerance).

6 See my workshop “Dramatic Interpretation in Multicultural Music Education!

7 At my University there are courses of integration for foreign students. We tried to integrate musical activity into these courses. The results of this experiments can be transformed into a model of general courses of integration for migrants: Their competence of multicultural activity can be trained by just accepting the diversity of the different migrant backgrounds of the people who participate in the course. If every participant just offers one music example which might be typical for him and his ethnic background, and if all the others listen to this music and ask, why this music is chosen by the one who presented it, this would be a thorough training in multicultural competence

8 If there is time left: The other examples is a Turkish or Kurdish Wedding. Such weddings are places and events of ethnic self-definition. In Germany every such event comprises at least 500 to 800 people, no matter if the parents of the couple are unemployed, on social support or are rather well-off. All the hundreds of participants together pay for the rent of the wedding-hall, the musicians and the food (Video 4a: Kurdish Wedding in Delmenhorst).

On the other side, the established German musical organizations do very little to open themselves towards cooperating with the rather informal musical life of the migrants. In 1999 I asked all 80 “Musikschulen” of Niedersachsen, what “foreign music” they offer in their curriculum. 64 Music Schools answered that there are once in a while courses with Latin Percussion, Panflute and Balaleika. However, over the rest of the country, only one single class was offered for bağlama (saz), an instrument which is very popular among Turkish migrants in Germany.

Remark: A German and augmented version of this essay: Gibt es noch eine "visionäre" interkulturelle Musikerziehung? In: Musik - Pädagogisch - Gedacht. Reflexionen, Forschungs- und Praxisfelder. Festschrift für Rudolf-Dieter Kraemer, ed. Martin D. Loritz et al. Wißner, Augsburg 2011, p. 54-67.